The New York Times

By Jonathan Kandell

June 15, 2019

Franco Zeffirelli, the Italian director renowned for his extravagantly romantic opera productions, popular film versions of Shakespeare and supercharged social life, died on Saturday at his home in Rome. He was 96.

His death was confirmed by a spokesman for the Franco Zeffirelli Foundation in Florence.

Critics sometimes reproached Mr. Zeffirelli’s opera stagings for a flamboyant glamour more typical of Hollywood’s golden era, while Hollywood sometimes disparaged his films as too highbrow. But his success with audiences was undeniable.

Beginning with his 1964 staging of Verdi’s “Falstaff,” his productions drew consistently large audiences to the Metropolitan Opera in New York over the next 40 years. His staging with Maria Callas of Verdi’s “La Traviata” in Dallas in 1958 and Giacomo Puccini’s “Tosca” at Covent Garden in London in 1962 “remain touchstones for opera aficionados and Callas cultists,” Brooks Peters wrote in a profile of Mr. Zeffirelli in Opera News in 2002.

Mr. Zeffirelli’s filming of Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” starring the teenage Olivia Hussey and Leonard Whiting, thrilled millions of young viewers who had been untouched by the bard. “I’ve made my career without the support of the critics, thank God,” he told Opera News.

Even for the hyperbolic world of opera, his sets and costumes could seem overdone. In Bizet’s “Carmen,” he populated the stage with horses and donkeys. The headdress he designed for the imperious princess in Puccini’s “Turandot” appeared to be on the verge of collapsing under its own weight. Mr. Zeffirelli’s 1998 revamping of “La Traviata” was savaged by the critics for its overwhelming décor.

“His new look at Verdi’s masterpiece remains waiting and ready for a cast strong enough in personality to compete with its director’s illusions of grandeur,” Bernard Holland wrote in The New York Times. Nonetheless, performances of the opera sold out.

Some divas adored Mr. Zeffirelli despite his reputation for focusing too much on the staging. The mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves recounted how he helped her create an interpretation of the headstrong gypsy in his 1996 production of “Carmen” that was hailed for years to come.

Mr. Zeffirelli convinced Ms. Graves that unlike the conventional view of Carmen as a carefree, liberated woman, she in fact lacked confidence and feared losing her freedom by falling in love.

“I had never thought of it that way,” Ms. Graves told The Times in 2002. “It began to open a window in my mind that I didn’t know existed. From that moment on I had to relearn and rethink everything. I felt that I had no idea who Carmen was. It changed my singing completely. And that was just in the first five minutes.”

A whirlwind of energy, Mr. Zeffirelli found time not only to direct operas, films and plays past the age of 80, but also to carry out an intense social life and even pursue a controversial political career. He had a long, tumultuous love affair with Luchino Visconti, the legendary director of film, theater and opera. He was a friend and confidant of Callas, Anna Magnani, Laurence Olivier, Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Liza Minnelli, Coco Chanel and Leonard Bernstein.

Twice elected to the Italian Parliament, Mr. Zeffirelli was an ultraconservative senator, particularly on the issue of abortion. In a 1996 New Yorker article, he declared that he would “impose the death penalty on women who had abortions.” He said his extreme views on the subject were colored by the fact that he himself was born out of wedlock despite pressure brought to bear on his mother to terminate her pregnancy.

Franco Zeffirelli was born in Florence on Feb. 12, 1923, a product of an extramarital affair. His father, Ottorino Corsi, was a respected wool and silk merchant but inveterate womanizer, and his mother, Alaide Garosi, was a fashion designer who owned a dressmaking shop. Both were married to others at the time.

By one oft-told account Mr. Zeffirelli was named by his mother. In those days in Italy children of purportedly “unknown” fathers were assigned surnames starting with a different letter each year. He was born in the year of Z. His mother chose Zeffiretti, drawing on a word, meaning little breezes, heard in an aria in Mozart’s opera “Così Fan Tutte.” A transcription error, however, rendered it Zeffirelli. One problem with the story is that “zeffiretti” does not appear in the libretto. “Aurette,” breezes, does.

He knew his father only “in flashes,” he told The Times in 2009.

“I remember this gentleman came, especially at night,” he said. “I woke up and saw this shadowy man naked in bed with my mother.”

By one account his mother placed him with a peasant family, then took him in herself two years later, after her husband died. After she died of tuberculosis a few years later, he was sent to live with a cousin of his father’s.

He went to school in Florence, at the venerable Accademia di Belle Arti. One of his earliest memories was emerging from school at the end of classes and being accosted in the street by his father’s wife. “Bastardino, little bastard, you little bastard!” the woman screamed, Mr. Zeffirelli recalled in a 1986 autobiography.

He was taken to his first opera by an uncle at age 8 and was so smitten by stage design that while his friends played games after school, he buried himself in his cardboard scenes for Wagner’s “Ring of the Nibelungs.”

His interest in Shakespeare was awakened by an older British woman, Mary O’Neill, who tutored him in English as a child and imbued him with ethical values that foiled the Fascist curriculum served up at school.

“She kept injecting in me the cult of freedom of democracy that remained in my DNA for the rest of my life,” Mr. Zeffirelli told Opera News.

She and her expatriate friends in Florence became the subjects of “Tea With Mussolini” (1999), his acclaimed autobiographical film starring Joan Plowright, Maggie Smith and Judi Dench.

He went on to study architecture at the University of Florence, until the onset of World War II interrupted his education. He joined Communist partisan forces, first fighting Mussolini’s Fascists and then the occupying Nazis. Captured by the Fascists, he was saved from the firing squad when his interrogator miraculously turned out to be a half brother whom he had never known. The half brother arranged his release.

After the war he resumed his architecture studies at the university, but theater remained his abiding interest. In the late 1940s, the director Luchino Visconti spotted Mr. Zeffirelli, blond and blue-eyed, working as a stagehand in Florence.

“I begged him, I showed to him my designs as a set designer, that was my dream,” Mr. Zeffirelli said.

A smitten Mr. Visconti gave him his big break in 1949, making him his personal assistant and set designer for his production of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire,” the first staging of the play in Italy.

The two became romantically involved and lived together for three years. In his autobiography, published in 2006, Mr. Zeffirelli wrote that he considered himself “homosexual,” disliking the term “gay” as inelegant.

For years, Mr. Zeffirelli was responsible for Visconti sets and costumes. “Luchino showed me the world of creativity in theater and films, how to conceive an idea and how to bring together a whole world of culture that could embody it,” Mr. Zeffirelli wrote in his autobiography. “In other words, how to direct.”

But Mr. Visconti sought to undermine his protégé’s attempts to strike out on his own. Directing his first play, a revival of Carlo Bertolazzi’s “Lulu” in Rome in the 1940s, Mr. Zeffirelli was appalled to discover Mr. Visconti in the audience leading a chorus of jeers. The incident, Mr. Zeffirelli wrote, was part of the long, painful break between the two men.

Several years ago, Mr. Zeffirelli adopted two adult sons — Giuseppe (known as Pippo) and Luciano — men he had known and worked with for years. They helped manage his affairs, and survive him.

“I missed my father when I was a child, I craved becoming a father myself,” he told The Times in 2009. “But the facts of life prevented me from doing it.”

Within a few years of the “Lulu” revival in Rome, Mr. Zeffirelli had established himself as an inspired director of operas and plays on the world’s leading stages. In 1959, in London, he directed the then little known Joan Sutherland in Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor,” getting her “to make sense of the Mad Scene,” wrote the composer Ned Rorem in a 1996 Times article, “by cupping her hand to her ear, heeding her alter ego as echoed by the schizophrenic flute.”

In 1960, at London’s Old Vic, Mr. Zeffirelli directed a very young Judi Dench in a celebrated “Romeo and Juliet.” But it was the film version, released in the United States in 1968, that achieved superstar status for Mr. Zeffirelli. Costing a mere $1.5 million, the film grossed more than $50 million.

“From Bronx to Bali, Shakespeare was a box-office hit,” wrote Mr. Zeffirelli.

Also extremely popular were his film adaptations of Shakespeare’s “The Taming of the Shrew” (1967) with Ms. Taylor and Mr. Burton, and “Hamlet” (1990) starring Mel Gibson.

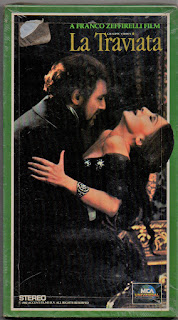

Mr. Zeffirelli scored further successes with film versions of operas, including “La Traviata” (1982), starring Teresa Stratas, and “Otello” (1986), with Plácido Domingo. His “Brother Sun, Sister Moon” (1973), depicting the life of St. Francis, and the television mini-series “Jesus of Nazareth” (1977) also drew huge worldwide audiences, if not always critical acclaim.

Mr. Zeffirelli did suffer a few memorable disasters. His 1963 directorial debut on Broadway — a production of Alexandre Dumas’s “The Lady of the Camellias,” starring Susan Strasberg — closed after four evenings. His production of Samuel Barber’s “Antony and Cleopatra,” a world premiere which inaugurated the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center in 1966, “entered the annals of famous flops,” the Times critic Anthony Tommasini wrote in 2003.

And in his memoir, Mr. Zeffirelli conceded that his misdirected 1981 film, “Endless Love,” starring the teenage Brooke Shields, would long be remembered as the butt of Bette Midler’s classic Oscar-night joke that year: “That endless bore.”

But these setbacks could not obscure Mr. Zeffirelli’s very considerable triumphs. When asked in 2002 why Mr. Zeffirelli’s production of Falstaff had endured at the Metropolitan Opera for almost four decades, Joseph Volpe, the Met’s general manager, replied:

“Now, it may be said by those great minds in the opera world, ‘Can’t the Met do any better than this?’ My answer is: ‘We don’t want to do better than this. As far as I’m concerned, this is the best.’ ”

Correction: June 15, 2019

An earlier version of this obituary misstated part of the title of a Mozart opera. It is “Così Fan Tutte,” not “Così Fan Tutti.”

No comments:

Post a Comment