Around 3000 years ago, several empires and kingdoms in the Mediterranean collapsed, with a group of sea-faring warriors implicated as the culprit. But new evidence shows that many of our ideas about this turbulent time need completely rethinking

By Colin Barras

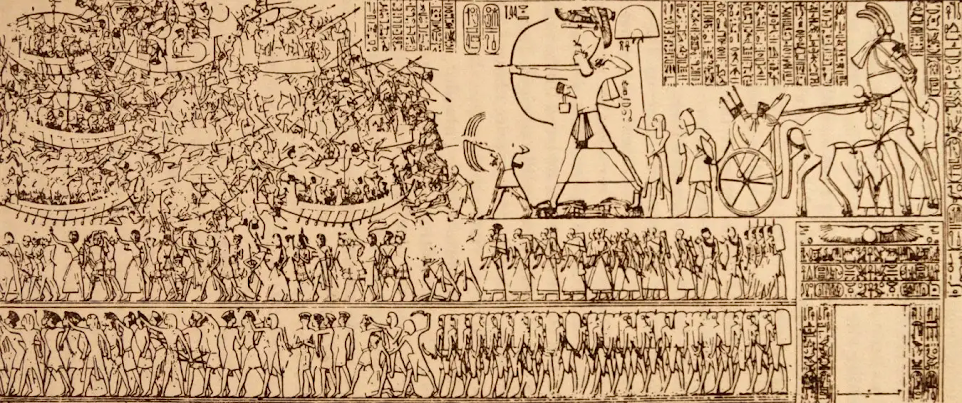

Ramesses III was one of Egypt’s great warrior pharaohs. A temple he built at Medinet Habu, near the Valley of the Kings, highlights why. On its walls, carvings tell the story of a coalition of fighters that swept across the eastern Mediterranean 3200 years ago, destroying cities, states and even whole empires. “No land could stand before their arms,” this account tells us. Eventually, the invaders – known today as the Sea Peoples – attacked Egypt. But Ramesses III succeeded where others had failed and crushed them.

In the 200 years since hieroglyphics were first deciphered, allowing us to read Ramesses III’s extraordinary story, evidence has come to light to corroborate it. We now know of numerous cities and palaces across the eastern Mediterranean that were destroyed around that time, with the Sea Peoples often implicated. So widespread was the devastation that, for one of the only times in history, several complex societies went into a steep decline from which they never recovered. Little wonder, then, that this so-called Late Bronze Age collapse has fascinated scholars for decades. So, too, has the identity of the mysterious sea-faring marauders.

Today, new genetic and archaeological evidence is giving us the firmest picture yet about what really went on at this dramatic time – and who, or what, was responsible. This shows that many of our ideas about the Sea Peoples and the collapse need completely rethinking. It also hints at a surprising idea: the end of civilisation might not always be as disastrous as we think.

Before the Sea Peoples arrived, life was good in the Late Bronze Age of the eastern Mediterranean – if you were an elite member of society, that is. During this period, between 1550 and 1200 BC, kings from Mycenaean Greece in the west of the region to the rulers of Babylonia in the east lived in opulent palaces, taking advantage of a thriving trade network to procure all the luxuries of the time, from gold and jewels to ivory and fine wines.

Then things fell apart. In Mycenaean Greece, where there were a handful of small kingdoms, the palaces were destroyed and the nature of society completely changed. “There was an end to fine craft production,” says Guy Middleton at Newcastle University, UK. The Mycenaean tradition of writing ended too, with their script – Linear B – falling out of use.

The chaos wasn’t confined to the Mycenaean world. Notably, the powerful, 450-year-old Hittite empire that controlled most of Anatolia (roughly corresponding to modern Turkey) fragmented. In fact, some researchers think that most cities along the Anatolian coast and down the eastern shores of the Mediterranean were destroyed. This included Ugarit, a city in what is now Syria – and here there seems to be clear evidence of what went wrong.

Several archives in cuneiform, another ancient writing system, have been unearthed during excavations at Ugarit, and some of the texts appear to be letters composed by Ugarit’s king, Ammurapi, just before the city’s downfall. In one, translated in 2016, the desperate ruler writes that “the enemy forces are stationed at Ra’šu [one of Ugarit’s ports]”.

Ancient Egyptian engravings

In light of such evidence, it is easy to see why many researchers think Ugarit was sacked by a seafaring force – most probably the Sea Peoples described in engravings on Ramesses III’s temple. These warriors were credited with incredible strength by the ancient Egyptians. “Not a single Egyptian foe has ever been assigned such powers… never has an enemy been described as the destroyer of empires,” wrote Shirly Ben Dor Evian at the University of Haifa, Israel, in a 2018 study of ancient Egyptian texts. But who were these people?

Even today, the question lacks a definitive answer, but a handful of ancient clues are helping to build a clearer picture. A good starting point are the battle scenes carved on the temple. These show that one group of fighters in the Sea Peoples coalition wore horned helmets and carried long swords and round shields. This gear – reminiscent of the stereotypical idea of a Viking warrior – is unlike anything used by combatants in the eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age. But it had been seen in Egypt before. Similar equipment was carried by invaders who had assaulted Egypt a century earlier, and who were depicted on monuments left by the pharaoh in charge at that time, Ramesses II, who named the attackers as the Šardana.

For obvious linguistic reasons, researchers suspected that the Šardana hailed from Sardinia, suggesting some Sea Peoples had roots in this island off Italy or southern Italy more generally. But we can’t be sure of the link, says Reinhard Jung at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. He points out that there are no Sardinian texts from that time, so we don’t know if the locals used the name Šardana to describe themselves. The archaeological evidence is largely lacking too. “There was an unfortunate religious habit in southern Italy not to place armour in the tomb,” says Jung, which means we don’t know whether warriors from this region really did wear horned helmets. Swords from the area do, however, look like those carried by the Šardana as depicted on the Egyptian monuments.

There are other reasons to suspect that the Sea Peoples coalition included a southern Italian contingent. Many settlements in that area were attacked and destroyed in the final centuries of the Bronze Age, possibly by invaders from northern Italy. And if the southern Italian settlements were destroyed, perhaps their inhabitants were forced to flee. Jung says it would make sense for them to sail to a region they knew, either to raid the land or to search for new homes.

The Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses III defeats the Sea Peoples in this 19th-century illustration of carvings on his temple

Significantly, in the past 20 years we have new evidence that the southern Italians traded with the eastern Mediterranean and so must have been familiar with the area. For example, we now know that a distinctive style of pottery that began appearing in Mycenaean Greece towards the end of the Bronze Age – known as handmade burnished ware – was southern Italian in origin. And in 2019, an analysis of ancient DNA showed that pig bones found at one Mycenaean palace had a genetic signature suggesting the animals came from Italy.

With evidence like this, a tentative explanation for the Late Bronze Age collapse emerges. The communities of southern Italy were uprooted towards the end of this period. They moved east and – either deliberately or inadvertently – destabilised the kingdoms of Mycenaean Greece (see map, below). As those so-called palace economies quickly descended into chaos, many Mycenaeans lost their homes too, swelling the ranks of the displaced. The coalition of migrants continued pushing along the coast in search of new homes, destroying cities and states in their path, before they met their match while attacking Egypt.

Ramesses III’s temple seems to provide more support for this narrative of destructive migrants. The pharaoh named one of the groups in the Sea Peoples coalition as the Peleset. Today, many researchers identify the Peleset with the Philistines, who lived in a region – Philistia – now chiefly encompassing the Gaza Strip and parts of southern Israel.

Importantly, it has long been suspected that the Philistines were foreign invaders who took Philistia by force roughly 3200 years ago. Moreover, many researchers argue that the Philistines hailed from Greece, because some of their pottery looks Mycenaean. In 2019, genetic evidence seemed to confirm this link. An analysis of ancient DNA showed that four infants who lived in Philistia about 3100 years ago had a genetic signature linked to places in southern Europe such as Greece and Sardinia, indicating a wave of immigrants to the region.

For decades, however, there has been no good explanation for why such chaos and mass migration would have unfolded quite so dramatically. But here, too, recent research provides some clues. Several studies have concluded that the Mediterranean experienced a centuries-long megadrought at the end of the Bronze Age. The suggestion is that this triggered chronic food shortages and social unrest – priming the region for the collapse of civilisations.

But, for a growing number of researchers, this sounds more like a Hollywood plot than an account of real history. They argue that a more critical examination of the evidence suggests there was, in fact, no destructive wave of migrants sweeping across the Mediterranean and no centuries-long drought. In fact, some even doubt there was a Late Bronze Age collapse in the sense of a single region-wide disaster. “People turned this up to 11, and we have to take it back down to 3,” says Jesse Millek at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

To begin with, Ramesses III’s evidence about the nature of the Sea Peoples becomes more opaque under cross-examination. There is notorious ambiguity in ancient Egyptian texts, which makes them tricky to interpret. Ben Dor Evian’s 2018 re-analysis suggests that the pharaoh actually meant the Sea Peoples were in fact employed by the Hittites, rather than destroying them. And a 2022 study made the case that the term Ramesses III used to describe the Sea Peoples chiefs suggests they were more likely to be leaders of bands of pirates than a formidable army.

Even with these more nuanced interpretations it is never wise to build the foundations of history on words approved by a pharaoh. Doing so would be the equivalent of a future historian trying to understand the 21st century world solely by reading an account endorsed by Russia’s president Vladimir Putin, says Sturt Manning at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. “It would give you an odd view of events,” he says.

Moreover, researchers have taken the accounts on Ramesses III’s temple and hyped them up further. Some have argued that the Sea Peoples were responsible for the destruction of the Mycenaean kingdoms and dozens of cities – including Ugarit – in the eastern Mediterranean. But Ramesses III mentioned few of these places in the list of sites he says the Sea Peoples laid to waste.

Worse, many of them may not have been razed at all. Over the past few years, Millek has re-examined the field notes taken years ago as these places were excavated. At most of them – including those in Philistia that the Philistines supposedly took by force – the evidence for destruction is weak. At Ekron in Philistia, for instance, there is just a single burned storage building. As such, Millek doubts the Sea Peoples were really a cataclysmic force.

What, then, did happen? By abandoning the story that the Sea Peoples were responsible for a wave of destruction, alternative explanations become available. These include the idea that each kingdom and city collapsed independently because of specific local factors.

At first glance, that sounds implausible: so much chaos occurring simultaneously is surely no coincidence. But, in reality, the timeline of these events was probably more relaxed than that. “The destructions in Mycenaean Greece could have taken place over 15 or 20 years,” says Helène Whittaker at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Across the region more broadly, it might have occurred over 50 years, says Manning – hardly evidence of a single, acute crisis.

Moreover, says Millek, for all we know there was a relatively high level of destruction throughout the 350 years of the Late Bronze Age, meaning it might not have been unusual for several cities to be under attack at any given time. Significantly, earlier this year researchers announced the discovery of a cuneiform tablet, unearthed in a Hittite city, which describes how “four cities, including the capital, Hattuša, are in disaster“. It was written 200 years before the Late Bronze Age collapse.

New analyses of ancient climate are also making a region-wide crisis seem less likely. Although some studies appear to show that the Mediterranean experienced a centuries-long drought that began roughly 3200 years ago, Manning says this idea is “misleading”. It is based in part on analyses of ancient pollen, which can reveal shifts in vegetation in response to changes in conditions. But most of these are low in resolution, with potentially decades separating data points, so they don’t provide a full picture. “It’s only when you have high-resolution sources, ideally annual data, that you see there’s a great deal more complexity,” says Manning.

So much chaos, simultaneously, is surely no coincidence?

Last year, he and his colleagues published a dataset capturing climatic conditions 3200 years ago near Hattuša. This came from analysing tree rings in ancient juniper logs to assess changes in rainfall from year to year. It showed there were plenty of “wet” years in Anatolia at the end of the Bronze Age.

The analysis did find evidence that Anatolia experienced a devastating, three-year drought between 1198 and 1196 BC, coinciding with the demise of the Hittite empire. But Manning and his colleagues concluded that this on its own probably doesn’t explain that collapse. It is significant, they argue, that the Hittite royal family had splintered a few decades earlier. This meant that the drought hit while the empire was politically weak and less able to cope with problems such as food shortages.

It isn’t just squabbling royals who can contribute to the fall of a civilisation. Middleton suspects that the general population, too, may sometimes play a part. For example, he says that when the Mycenaean palace states collapsed, many of the non-palatial rural communities of Greece continued apparently unaffected.

Re-examining the evidence

We don’t know why, but one possibility – first suggested by Jung – is that it was the general population, rather than invading Sea Peoples, who destroyed the palaces. The idea is that they did so because the ruling elites had become too oppressive. “It might be that most people were glad to be rid of the palaces,” says Whittaker.

This take on the Late Bronze Age collapse is arguably the most radical of all. We might like to imagine that a society capable of producing opulent architecture and written records is fundamentally better than a society lacking these features. As such, it is tempting to interpret the disappearance of sophisticated societies as evidence of an unexpected and unwanted catastrophe. But we forget there is an alternative, says Millek: that people may choose to stop building palaces and keep written records because they want a more egalitarian and uncomplicated society.

“Even today, many people say they would love to give up the trappings of modern life and go back to something simpler,” says Millek. It is conceivable that some of the Bronze Age inhabitants of the eastern Mediterranean, including the Sea Peoples, felt the same way.

We still have plenty to learn about the dramatic events at the end of the Bronze Age. But as the evidence continues to accumulate, we may finally be able to acquit the Sea Peoples. It is possible they have been framed for “crimes” that may never have happened.

No comments:

Post a Comment