By Raquel Brandao Earth.com staff writer

An unmanned submarine mapping West Antarctica’s Dotson Ice Shelf reported strange under-ice structures, then went silent ten miles beneath it. The vehicle, called Ran, had spent weeks scanning an ice area roughly fifty square miles, revealing patterns that upend simple melt models.

Her research focuses on how ocean currents erode ice shelves from below, changing glacier stability and future sea level.

Ran is an autonomous underwater vehicle, a robot submarine that navigates alone under ice for hours.

During a 2022 campaign, Ran spent 27 days weaving under Dotson’s floating ice, eventually reaching about eleven miles into the hidden cavity.

The mission aimed to explain the sharp contrast between Dotson’s thick, slow-melting eastern side and its thinner, faster-melting western side.

In the east and center, Ran saw icy terraces stacked like steps, while the west looked smoother, with channels and scooped depressions.

None of these terraces or teardrop pits show up on satellite images, so they had remained completely hidden until Ran’s mission.

Satellite altimetry over Dotson shows that melt channels lose ice at about 40 feet per year, a thinning pattern linked to warm water.

Analysis of measurements under Dotson indicates that this ice shelf added 0.02 inches to sea level between 1979 and 2017.

The under-ice maps show that this warm inflow focuses erosion on Dotson’s western side, while colder water leaves the eastern flank protected.

In the fast outflow region, currents create smoother surfaces with grooves, where shear-driven turbulence, mixing caused by sliding water layers, drives rapid melting.

Some pits are teardrop shaped, 984 feet long and 164 feet deep, carved by currents near the ice base.

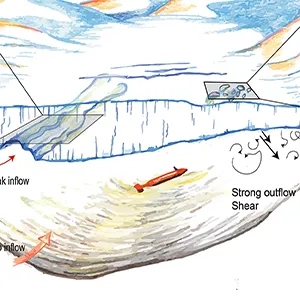

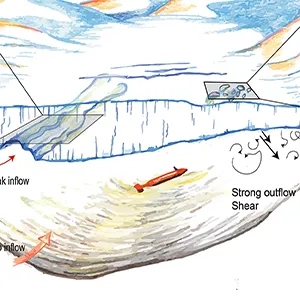

Sketch showing the processes discussed in the paper on the Dotson Ice Shelf in Antarctica. Note that the vertical scale is exaggerated. Credit: Science/ITGC. Click image to enlarge.

Sketch showing the processes discussed in the paper on the Dotson Ice Shelf in Antarctica. Note that the vertical scale is exaggerated. Credit: Science/ITGC. Click image to enlarge.

Much of that loss comes from West Antarctica, where ice shelves like Dotson float above deep basins that warm currents can reach.

When those floating shelves thin or break, they stop bracing the land-based ice behind them, so glaciers accelerate and sea levels climb faster.

Understanding how warm water eats away at Dotson’s base now helps researchers judge how quickly distant glaciers might respond as the climate warms.

Instead, the vehicle relied on navigation systems and acoustic instruments to track its position against the seafloor and the underside of the ice.

Typical missions ranged between several hours and more than a day, meaning problems deep under the ice stayed invisible until Ran surfaced again.

Despite those hazards, the team completed 14 successful under-ice missions with Ran in 2022, bringing back a dataset for glaciologists and oceanographers.

“To see Ran disappear into the dark, unknown depths below the ice, executing her tasks for over 24 hours without communication, is of course daunting,” said Wåhlin.

When Ran did not appear at the pickup point, attempts to contact the vehicle failed and searches found no signals or debris.

Because there was no feed, the team can speculate about the cause, ranging from mechanical failure to a collision with ice ridges.

Those maps show that the underside of an ice shelf can host terraces, channels, fractures, and teardrops, each responding differently to currents.

Incorporating terraces, fractures, and melt channels into models should help narrow predictions of how quickly West Antarctica might lose ice in future climates.

For now, the detailed maps Ran sent home are a rare window on Antarctica’s hidden melt machinery, reminding scientists how much remains unexplored.

The study is published in Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

An unmanned submarine mapping West Antarctica’s Dotson Ice Shelf reported strange under-ice structures, then went silent ten miles beneath it. The vehicle, called Ran, had spent weeks scanning an ice area roughly fifty square miles, revealing patterns that upend simple melt models.

Mission beneath Dotson ice shelf

The work was led by Anna Wåhlin, a professor of oceanographic physics at University of Gothenburg, coordinating the Ran missions in West Antarctica.Her research focuses on how ocean currents erode ice shelves from below, changing glacier stability and future sea level.

Ran is an autonomous underwater vehicle, a robot submarine that navigates alone under ice for hours.

During a 2022 campaign, Ran spent 27 days weaving under Dotson’s floating ice, eventually reaching about eleven miles into the hidden cavity.

The mission aimed to explain the sharp contrast between Dotson’s thick, slow-melting eastern side and its thinner, faster-melting western side.

Strange shapes under the ice

Using sonar, Ran mapped 54 square miles of ice underside beneath Dotson Ice Shelf. The maps revealed flat plateaus, terraced steps, and teardrop-shaped pits, all carved by basal melt, melting that attacks the ice from below.In the east and center, Ran saw icy terraces stacked like steps, while the west looked smoother, with channels and scooped depressions.

None of these terraces or teardrop pits show up on satellite images, so they had remained completely hidden until Ran’s mission.

Warm deep water, uneven melting

Around Antarctica, Circumpolar Deep Water, a warm salty current from the Southern Ocean, moves onto the shelf and melts ice shelves from below.Satellite altimetry over Dotson shows that melt channels lose ice at about 40 feet per year, a thinning pattern linked to warm water.

Analysis of measurements under Dotson indicates that this ice shelf added 0.02 inches to sea level between 1979 and 2017.

The under-ice maps show that this warm inflow focuses erosion on Dotson’s western side, while colder water leaves the eastern flank protected.

Terraces, teardrops, and turbulence

Where currents move slowly, the base of the ice looks like stacked ledges, formed as melting eats away flats and leaves small steps.In the fast outflow region, currents create smoother surfaces with grooves, where shear-driven turbulence, mixing caused by sliding water layers, drives rapid melting.

Some pits are teardrop shaped, 984 feet long and 164 feet deep, carved by currents near the ice base.

Elsewhere, the terraced plateaus probably record bursts of slightly warmer water entering the cavity, slowly peeling away layers of ice over many years.Fractures that widen from belowRan also imaged full-thickness fractures that slice through the ice shelf, many of them widened and smoothed at their bases by melting.

Satellite records show that some of these cracks have been open since the 1990s, and those older fractures carry the deepest melt scars.

In these narrow slots, faster moving water can channel extra heat against the ice walls, turning fractures into hidden highways for ice loss.

Because most computer models treat melt in broad strokes, they often overlook how fractures and channels steer warm water and concentrate damage.

Satellite records show that some of these cracks have been open since the 1990s, and those older fractures carry the deepest melt scars.

In these narrow slots, faster moving water can channel extra heat against the ice walls, turning fractures into hidden highways for ice loss.

Because most computer models treat melt in broad strokes, they often overlook how fractures and channels steer warm water and concentrate damage.

Sketch showing the processes discussed in the paper on the Dotson Ice Shelf in Antarctica. Note that the vertical scale is exaggerated. Credit: Science/ITGC. Click image to enlarge.

Sketch showing the processes discussed in the paper on the Dotson Ice Shelf in Antarctica. Note that the vertical scale is exaggerated. Credit: Science/ITGC. Click image to enlarge.Implications for future sea levels

Combined satellite and climate data show that Antarctic ice loss has added about 0.55 inches of sea level since 1979.Much of that loss comes from West Antarctica, where ice shelves like Dotson float above deep basins that warm currents can reach.

When those floating shelves thin or break, they stop bracing the land-based ice behind them, so glaciers accelerate and sea levels climb faster.

Understanding how warm water eats away at Dotson’s base now helps researchers judge how quickly distant glaciers might respond as the climate warms.

Dotson Ice Shelf difficulties

Ran worked without real time contact, because radio waves and GPS signals cannot pass through hundreds of feet of solid ice.Instead, the vehicle relied on navigation systems and acoustic instruments to track its position against the seafloor and the underside of the ice.

Typical missions ranged between several hours and more than a day, meaning problems deep under the ice stayed invisible until Ran surfaced again.

Despite those hazards, the team completed 14 successful under-ice missions with Ran in 2022, bringing back a dataset for glaciologists and oceanographers.

When Ran submarine disappeared

When the researchers came back to Dotson, Ran was sent on a mission beneath ice to extend maps and measurements.“To see Ran disappear into the dark, unknown depths below the ice, executing her tasks for over 24 hours without communication, is of course daunting,” said Wåhlin.

When Ran did not appear at the pickup point, attempts to contact the vehicle failed and searches found no signals or debris.

Because there was no feed, the team can speculate about the cause, ranging from mechanical failure to a collision with ice ridges.

Lessons from the Dotson Ice Shelf

Despite the loss, Ran’s earlier missions transformed the team’s view of how ice and ocean interact in this remote cavity.Those maps show that the underside of an ice shelf can host terraces, channels, fractures, and teardrops, each responding differently to currents.

Incorporating terraces, fractures, and melt channels into models should help narrow predictions of how quickly West Antarctica might lose ice in future climates.

For now, the detailed maps Ran sent home are a rare window on Antarctica’s hidden melt machinery, reminding scientists how much remains unexplored.

The study is published in Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment